Rare Pigments Used in Medieval Manuscript Art: Sourcing and Significance

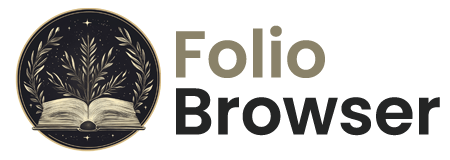

In medieval manuscript art, rare pigments such as ultramarine, verdigris, and red dyes like cochineal played vital roles. Ultramarine, sourced from Afghan lapis lazuli, was as costly as gold, symbolizing wealth and devotion. Verdigris, made from copper exposed to vinegar, added rich greens through skilled craftsmanship. Reds from madder roots or exotic insects highlighted power and emotion. Gold leaf application signaled the manuscript's significance with its divine glow and required great skill to apply. These pigments didn't just color pages; they spoke of status, luxury, and artistry. By exploring more, you'll uncover the deeper layers of their cultural impact.

Ultramarine and Lapis Lazuli

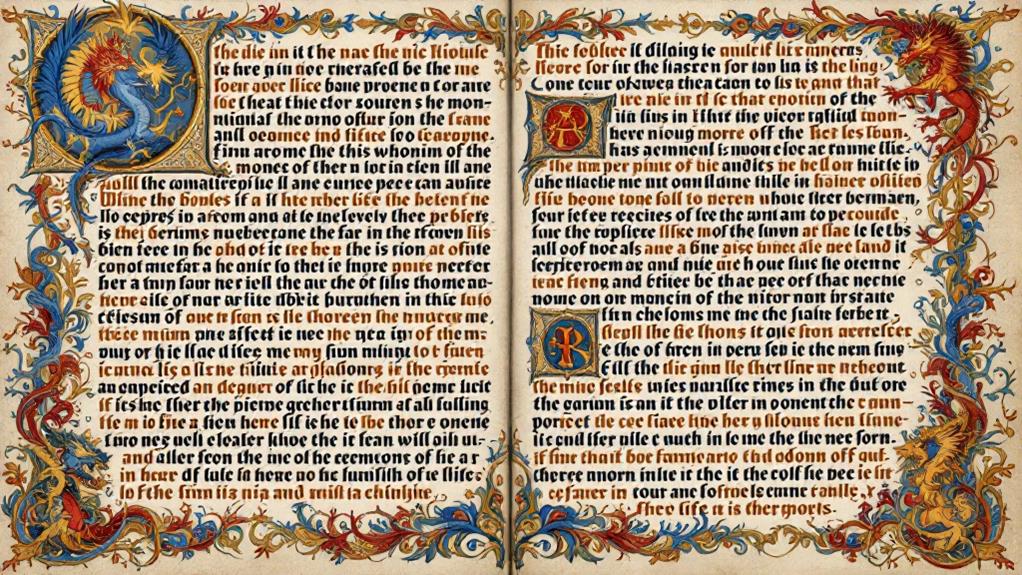

Among the most prized pigments in medieval manuscript art, ultramarine stands out for its vivid blue hue. You might wonder how such a striking color found its way into those intricate manuscripts. The secret lies in ultramarine sourcing, which was both a careful and costly process. Derived from the semi-precious stone lapis lazuli, ultramarine was more than just a color; it was a symbol of wealth and importance. Lapis lazuli significance can't be overstated—it was mined primarily in what is now Afghanistan, making the pigment as rare as it was precious.

To acquire ultramarine, artisans would grind lapis lazuli into a fine powder, extracting the purest blue. This extensive labor made ultramarine more expensive than gold at times, reflecting its value in art and beyond. When you see a manuscript adorned with ultramarine, you're witnessing a piece of history that speaks to the dedication and resources invested in its creation. The choice to use ultramarine wasn't merely aesthetic; it was a statement of status and reverence. As you investigate these manuscripts, recognize the skill and significance behind every brushstroke of this extraordinary blue.

Verdigris and Copper Sources

While ultramarine captivated with its deep blue brilliance, the allure of green in medieval manuscripts came from verdigris, a pigment derived from copper. You might find it fascinating that this lively green was not simply extracted from nature but required a thorough process. The creation of verdigris involved exposing copper to acetic acid, often from vinegar, which then reacted to form a greenish patina. This pigment processing was an art in itself, allowing scribes to produce a striking green that stood out in manuscript illustrations.

Copper mining played a key role in the availability of verdigris. Throughout Europe, regions known for mining copper, such as those in Central Europe, provided the raw material fundamental for this pigment. Without these mining activities, the supply of verdigris would have been limited, impacting the rich greens that adorned medieval texts.

As a collector or enthusiast of medieval art, understanding verdigris gives you insight into the lengths artisans went to achieve such lively colors. They sourced materials from the earth, manipulated them through careful processes, and created pigments that have captivated viewers for centuries. This dedication highlights the intersection of science and art in medieval times.

Red Pigments and Exotic Dyes

Delving into the world of medieval manuscripts, you'll uncover the striking reds that graced their pages, made possible by the use of red pigments and exotic dyes. Among these, madder root offered a brilliant hue known for its durability and was a staple in the artist's palette. This plant-based dye, extracted from the roots of the Rubia tinctorum, provided a rich red that was both affordable and relatively easy to source.

Equally fascinating is the cochineal extract, derived from insects native to Central and South America. Though it became more prevalent after the medieval period, its lively carmine red captivated artists and patrons alike. Another remarkable source of red was the kermes insects, found on Mediterranean oak trees. These tiny creatures produced a deep crimson dye highly prized for its intensity and rarity, often reserved for the most luxurious manuscripts.

Red ochre, a naturally occurring earth pigment, also played a significant role. Its warm, earthy tones added depth and contrast to illustrations. By skillfully combining these sources, medieval artists crafted pages that not only pleased the eye but also reflected the rich tapestry of available resources and techniques.

Gold Leaf and Its Impact

Turning from the lively reds that adorned medieval manuscripts, the use of gold leaf stands out as a tribute to the opulence and skill of the period's artists. As you investigate these illuminated texts, you'll notice how gold leaf applications were carefully crafted to catch light, enhancing the manuscript's visual allure. Gold's reflective quality wasn't just decorative; it added depth and dimension to the illustrations, making them appear almost alive.

In medieval times, the creation and application of gold leaf involved specialized techniques safeguarded by historical guilds. These guilds guaranteed that only skilled artisans could work with this precious material, maintaining high standards and protecting trade secrets. You can see how gold leaf was not just a pigment but a symbol of prestige and craftsmanship.

Consider the following impacts of gold leaf in manuscript art:

- Visual Impact: Gold leaf heightened the manuscript's aesthetic, setting it apart from others with an unmatched brilliance.

- Technical Skill: Artists demonstrated their mastery through precise application, reflecting their expertise and dedication.

- Economic Symbolism: The use of gold indicated wealth and status, underscoring the manuscript's importance and value.

Cultural and Symbolic Meanings

Gold leaf in medieval manuscripts wasn't just about visual splendor; it carried deep cultural and symbolic meanings. When you look at these ancient texts, you're not just seeing decorative art but a reflection of medieval society's values and beliefs. Gold, a rare and precious metal, symbolized divine light and eternal glory. By incorporating gold into manuscripts, scribes and artists aimed to enhance the text's status, emphasizing its religious and spiritual importance. This wasn't merely decoration; it was a symbolic representation of the text's sacred nature.

Furthermore, each pigment used in these manuscripts held its own cultural significance. Ultramarine blue, for instance, was derived from lapis lazuli, a stone more valuable than gold at the time. Its use signified the importance of the content and the wealth or status of the manuscript's patron. Reds, often achieved through cinnabar or vermilion, symbolized power and passion, highlighting key figures or moments within the text. By understanding these symbols, you can see how medieval artists communicated messages beyond the written word, using color and materials to convey deeper meanings and reflect the cultural landscape of the time.